I believe resistance is futile if someone is bent on spying on you; there’re both serious and creative ways to go about it. Talking to your processor, behind your back, isn’t the primary or only means. Our’s is a golden age where corporates and government agencies stoop low enough to pry into bedrooms. Did you know that almost all machines1 you own have a processor aside from the one you paid for? It controls your processor (host) and won’t listen to you.

- Unbeknownst to the host, it runs out-of-band, on a separate chip

- It has unfettered access to any memory region; it runs at ring level −32

- It can run even when your machine is in stand-by

- It runs an OS and a TCP/IP server on certain ports bypassing any firewall in the host

- You would never know even if you’re spied on

- Can’t be terminated

- It controls the host’s boot cycle

A processor inside your processor, having its own operating system3, running services, buried very deep within and can’t be switched completely off – it’s needed to even bring up your processor during boot. I’m talking about the Intel ME — a backdoor that’s built into Intel processors; it’s inner workings known only to Intel who refuses divulging anything about it in the name of security4. What’s that? Yeah, I too went “I’m lucky! I own an AMD machine”. Well, look up PSP; it’s AMD’s ME. I think it’s clear by now such

back doors would exist even on mobile and server processors. It is just matter of time before they’re exposed.

Motive

Some bright minds have found a way to neutralize Intel’s backdoor5 i.e. not completely kill it, but make it harmless. Now neutralizing just your MEs isn’t going to stop your other machines from prying. Security experts and the paranoids will rightfully suggest

If you really want to be secure, go back to the cave. Use pen and paper; burn it, when you’re done!

Knowing it’s beyond me, why am I still doing it? Well definitely not for security6, but the hacker in me would like to own his toys – a reasonable expectation. A stranger shouldn’t tell you how to use your pen; even worse, use it behind your back routinely. It’s as simple as that. It’s probably one of the reasons7 I’m a FOSS loyalist.

I don’t want some processor, I didn’t pay for, to drain my laptop power, or steal data for some merchant who wants to sell stuff that I don’t want.

If this makes sense then you should clean your machine too, but at your own risk. Make sure you read the ME Cleaner guides, check versions and compatibilities then proceed cautiously. Basically, we’re going to do a BIOS firmware update8. Just that it’s not done internally using software but externally with a cheap BIOS programmer. How come re-programming the BIOS firmware shuts the backdoor? When you cold boot your processor, it starts with an amnesia and so it always starts with the BIOS boot program. In this program, there’s a hidden kill-switch for the back door: the HAP/AltMeDisable bit. If set, ME will just boot the host and halt.

Let’s get on with it!

Connect

You should just be able to physically access your motherboard; no soldering involved.

Tools

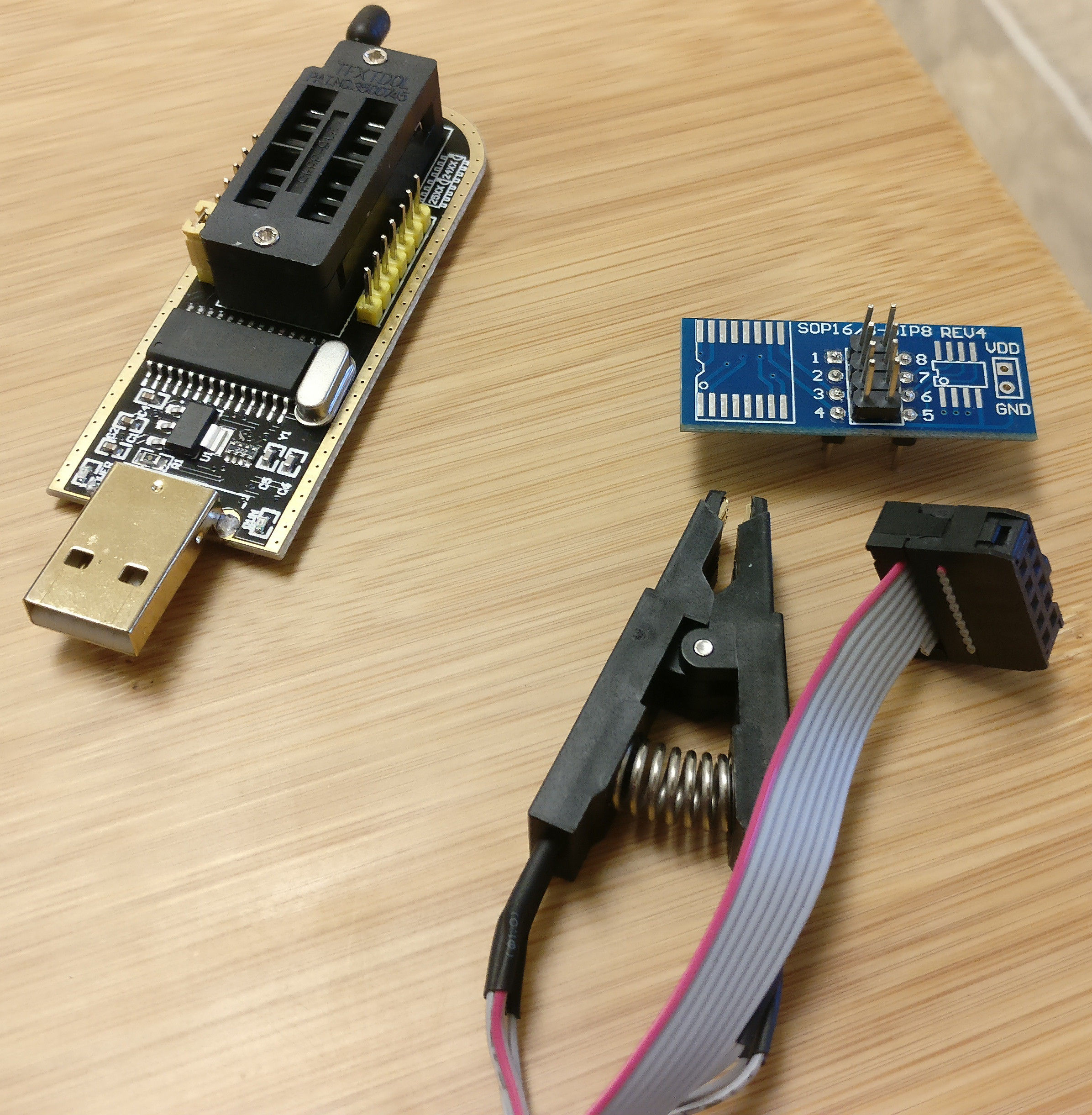

USB Programmer CH341A (left), SOP8 clip (bottom), SOP16/8-DIP8 board (top)

CH341A (Black) is a cheap9 USB SPI chip programmer. The SOP8 clip – that saves you from removing and re-soldering the BIOS chip – is sold separately. Make sure you buy the clip that comes with a SOP16/8-DIP8 board; this proxies as the BIOS chip going into the programmer’s slot. Take note

- The first bit is denoted on the BIOS chip-top with a circle marking.

- Make sure the clip’s red line, denoting the first bit, matches with this circle i.e. first on chip is connect to the first on clip when clipping.

- Connect the wire end of the clip to the board such that the first bits match – the board has all bit pins marked.

- Usually a 10-bit bus cable is used as the connector; notice that bits 9 and 10 are cut out.

- Look at the CH341A programmer board for a drawing about the 25 SPI BIOS chip layout. This should also have the circle marking.

- Connect the board-end of the clip such that its first and the SPI’s first bits match.

My Setup

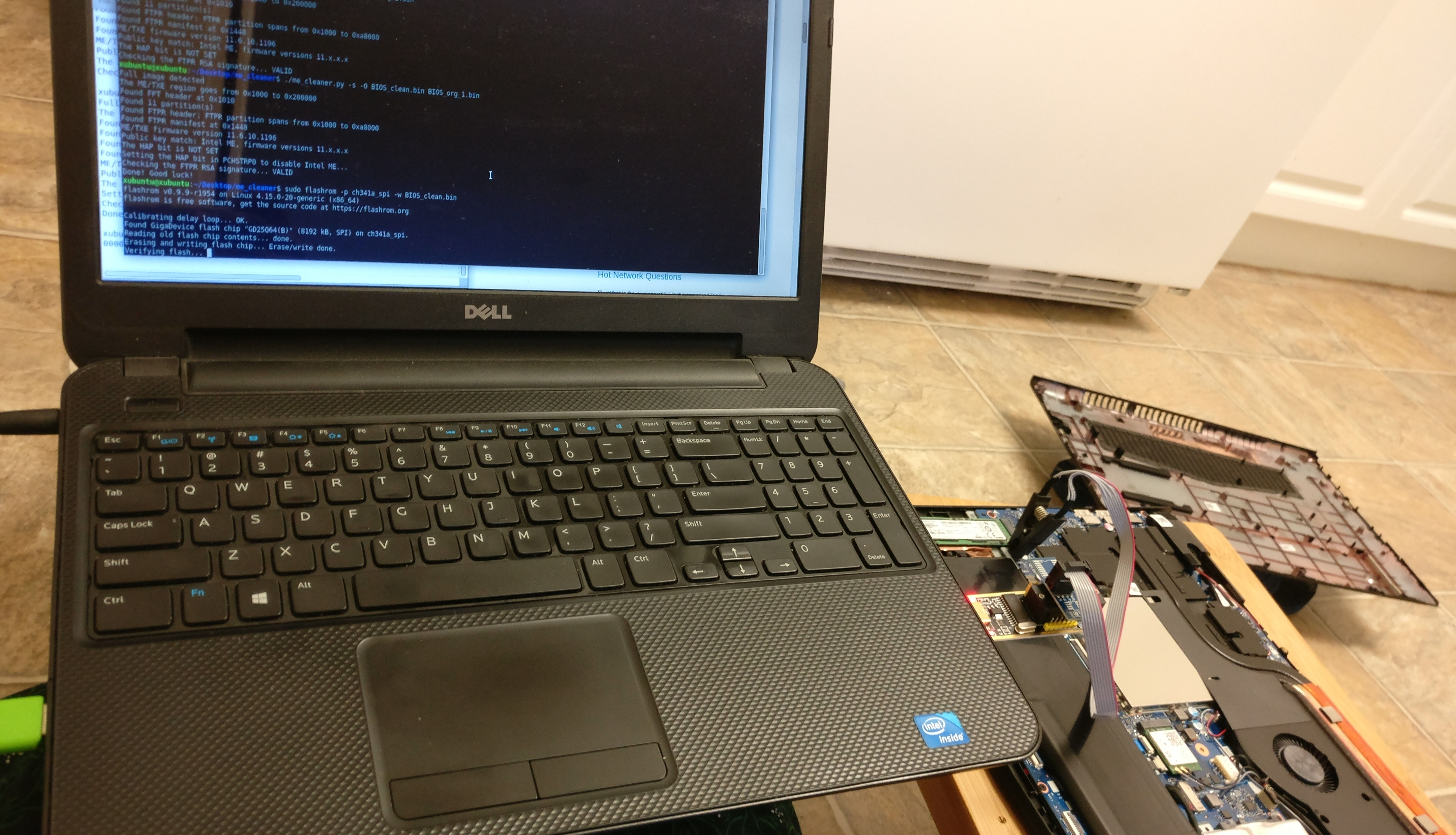

Connect the programmer’s USB to a Linux machine; I used a Xubuntu bootable USB to convert my old Windows 10 laptop. You’re all set hardware-wise. Run lsusb on the terminal and make sure you see something like

BUS 008 Device 012: ID 1a86:5512 QinHeng Electronics CH341 in EPP/MEM/I2C mode, EPP/I2C adapterThis means your Linux machine successfully detects the programmer.

Backup

Install flashrom; your distro’s package repository will definitely have this nifty tool. Make sure the chip is recognized by it:

$ sudo flashrom --programmer ch341a_spi -r BIOS_org.bin

flashrom v0.9.9-r1954 on Linux 4.15.0-20-generic (x86_64)

flashrom is free software, get the source code at https://flashrom.org

Calibrating delay loop... OK.

Found GigaDevice flash chip "GD25Q64(B)" (8192 kB, SPI) on ch341a_spi.

Reading flash... done.It should be able to auto-detect the chip and give you a full dump of the chip contents. If it says no devices were found, re-connect the clip; loose-contacts are common with these clips. Get two dumps and binary-compare them to make sure the connection was fine and the images are valid.

If there’re multiple SPI chips on your motherboard, make sure you get the right one i.e. the BIOS image you get from your OEM should have around the same size as the dump you just made.

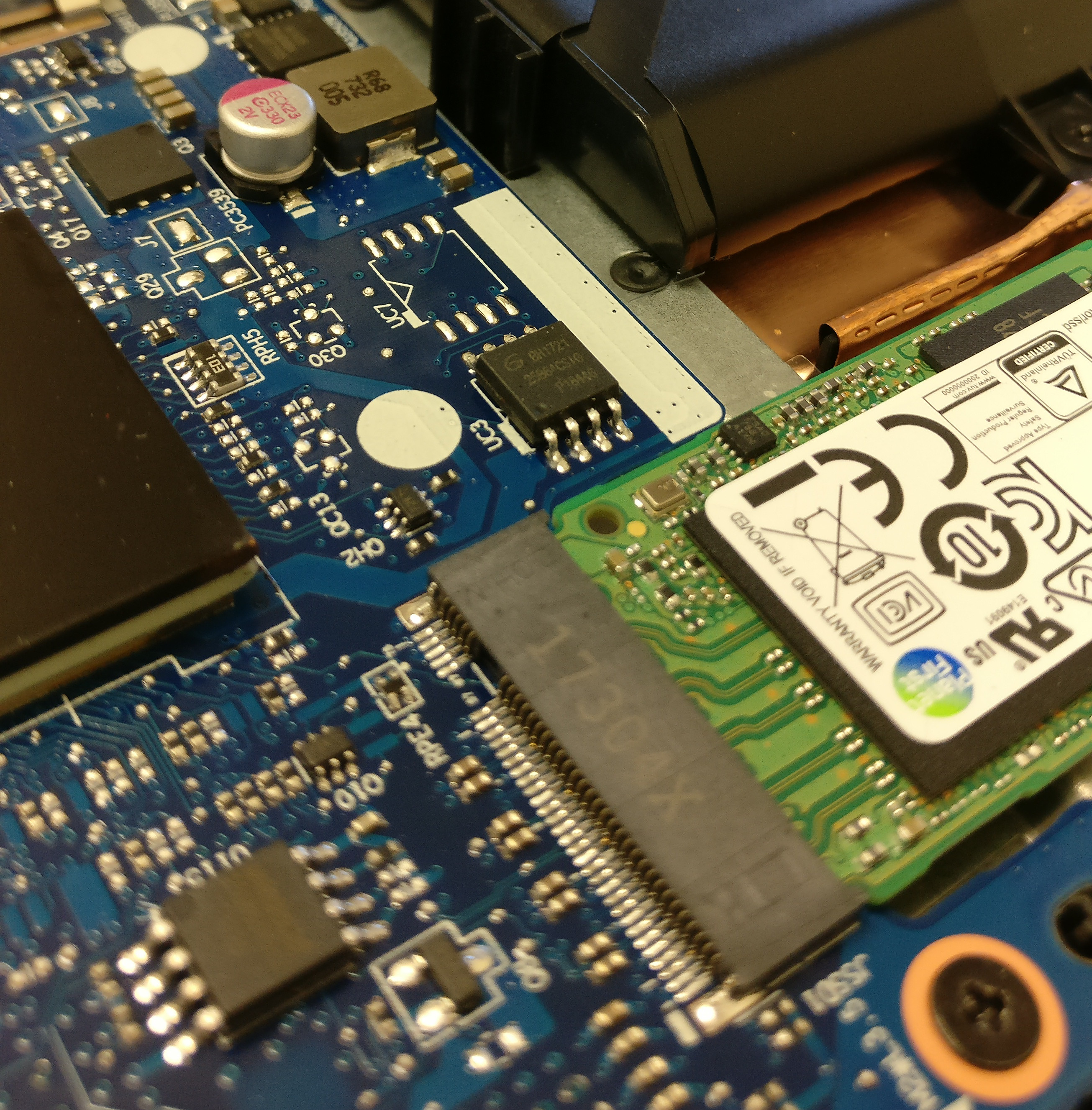

Eeny, meeny, miny, moe

1 MiB Winbond EEPROM chip (left-bottom) was a red herring. 8 MiB GigaDevice GD25Q64(B) BIOS chip (centre) was the one.

Run me_cleaner on the dump to verify it:

$ ./me_cleaner.py -c BIOS_org.binYou should get a valid output. You might also check it with the ifdtool from the coreboot repo: ifdtool -d BIOS_org.bin.

Clean

Run me_cleaner with the soft-clean option. It’s the safest; others wipe out the Intel ME module regions from the firmware; this one simply sets the bit.

$ ./me_cleaner.py -s -O BIOS_clean.bin BIOS_org.bin

Full image detected

The ME/TXE region goes from 0x1000 to 0x200000

Found FPT header at 0x1010

Found 11 partition(s)

Found FTPR header: FTPR partition spans from 0x1000 to 0xa8000

Found FTPR manifest at 0x1448

ME/TXE firmware version 11.6.10.1196

Public key match: Intel ME, firmware versions 11.x.x.x

The HAP bit is NOT SET

Setting the HAP bit in PCHSTRP0 to disable Intel ME...

Checking the FTPR RSA signature... VALID

Done! Good luck!It should set the AltMeDisable (or HAP) bit and wish you luck!

Flash

Flash the cleaned image back on to the SPI chip

$ sudo flashrom --programmer ch341a_spi -w BIOS_clean.bin

flashrom v0.9.9-r1954 on Linux 4.15.0-20-generic (x86_64)

flashrom is free software, get the source code at https://flashrom.org

Calibrating delay loop... OK.

Found GigaDevice flash chip "GD25Q64(B)" (8192 kB, SPI) on ch341a_spi.

Reading old flash chip contents... done.

Erasing and writing flash chip... Erase/write done.

Verifying flash... VERIFIED.It will first take a back-up for disaster-recovery. It’ll also see if it could optimize by not writing portions that don’t differ. Then it’ll write and verify if the image and the chip contents match! Quite a thorough piece of software; nice :)

Verify

Now for the moment of truth! Disconnet the clip, restart your machine. The machine should boot in to the OS normally. That isn’t all: make sure you use it for more than 40 mins and if nothing goes wrong, yay! You’ve successfully neutralized the backdoor! 🖖

On *nix, /dev/mei0 would no longer exist. Also the MEI entry should no longer show up for lspci. A more through way is intelmetool -s.

For Windows, get the right version of Intel ME System Tools

$ MEInfoWin64.exe -FWSTS

Intel(R) MEInfo Version: 11.8.50.3460

Copyright(C) 2005 - 2017, Intel Corporation. All rights reserved.

FW Status Register1: 0x80022004

FW Status Register2: 0x304D0116

FW Status Register3: 0x00000020

FW Status Register4: 0x00086000

FW Status Register5: 0x00000000

FW Status Register6: 0x40000004

CurrentState: Disabled

ManufacturingMode: Disabled

FlashPartition: Valid

OperationalState: Transitioning

InitComplete: Initializing

BUPLoadState: Success

ErrorCode: Disabled

ModeOfOperation: Alt Disable Mode

SPI Flash Log: Not Present

FPF HW Source value: FPF HW Not Set

ME FPF Fusing Patch Status: ME FPF Fusing patch NOT supported in this FW Version

Phase: BringUp

ICC: Valid OEM data, ICC programmed

ME File System Corrupted: No

PhaseStatus: UNKNOWN

FPF and ME Config Status: MatchYou can also verify that in the Device Manager, under System devices, the Intel(R) Management Engine Interface no longer shows up. Make sure you uninstall any ME-related software10.

Finally, be a good team player and report your success!

References

- Intel x86s hide another CPU that can take over your machine

- The Intel Management Engine: an attack on computer users’ freedom

- Deep dive into Intel Management Engine Disablement

- Disabling Intel ME 11 via undocumented mode

- Sakaki’s EFI Install Guide/Disabling the Intel Management Engine

- How to become the sole owner of your PC

- Intel ME Myths and Reality

- Me Cleaner’s external flashing guide

P.S.

This machine has CSME 11 since it is a Kaby Lake. Processors with older ME versions have much lesser security that this external flashing isn’t needed but is a lot cleaner. The OEM’s BIOS firmware upgrade utility usually works. I had a fun time cleaning my older laptop having ME 8.

the ones with micro-processor(s) ↩︎

Negative ring levels are below the kernel which is at 0. Lesser is deeper. ↩︎

MINIX OS, written by the same guy who flamed Linus Torvalds for writing a monolithic kernel. In some sense the microkernel design won since it’s now the most used OS 😉 ↩︎

Security by obscurity – the worst form of security, as opined by security experts. ↩︎

Sorry AMD owners; a consoling factor, however, is apparently PSP is much less capable than ME. ↩︎

Heck! I wouldn’t be blogging about it if that’s the case, would I now? ↩︎

Another reason is, of course, its superior engineering, better science and execution that stands the test of time, despite contributors not being paid engineers. Beat that corporates! ↩︎

Just that it’ll be a non-OEM update this time. ↩︎

Decent quality ones costed around $15 together ↩︎

There are reports of ME software resetting the bit and resurructing the parasite ↩︎